The Intuition Space

The Intuition Space

The Films and Writings of Gregory J. Markopoulos

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Lysis, 1948, 30 min

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Bliss, 1967, 6 min

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Sorrows, 1969, 6 min

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Eniaios, 1947-91, c.30 min (excerpt)

Introduced by Robert Beavers

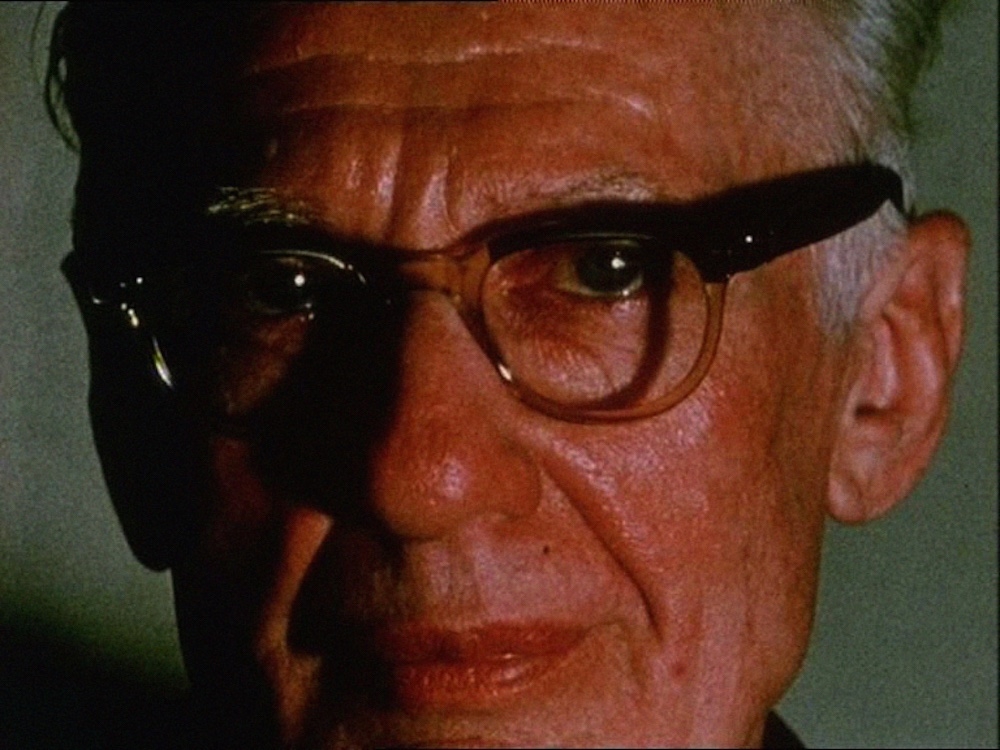

Gregory J. Markopoulos (born 1928, died 1992) was the son of Greek immigrants from the Peloponnesus and spoke only Greek until the age of six. The ancient legends and orthodox spirituality of that tradition would prove a grounding matrix for the rest of his life. He was fascinated by the idea of synesthesia, the confusion and correspondence between impressions of different senses that had pre-occupied already many Romantic artists. In the last ten years of his life, Markopoulos toiled over Eniaios, another, and the ultimate, reworking of his entire earlier film output. A completely silent eighty-hour long, epic re-configuration of his previous works; it is to be seen ideally over several weeks, in a yearly summer festival held at the Temenos, a special open-air cinema theatre dedicated to Markopoulos’s works and those of Robert Beavers. (text based on an essay by Kirk Alan Winslow)

Markopoulos called Lysis “a study in stream-of-consciousness poetry of a lost, wandering, homosexual soul” and felt that the film foreshadowed his famous work The Illiac Passion.

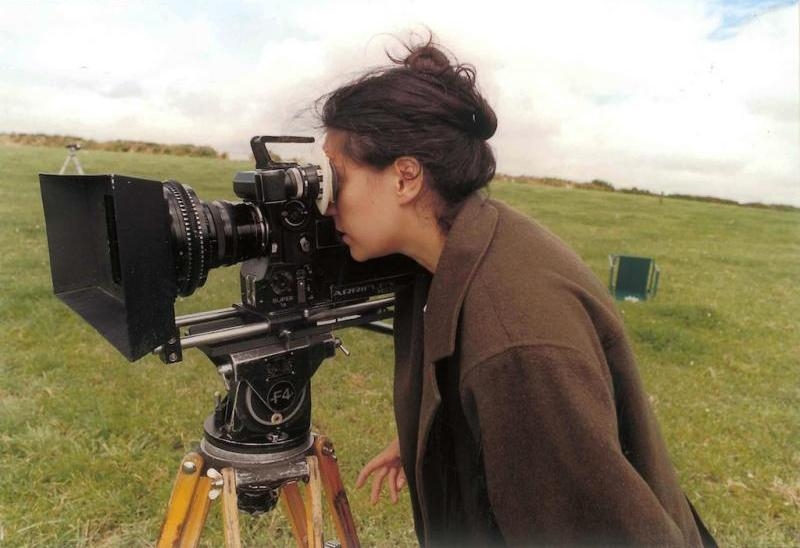

Bliss is a portrait of the interior of a Byzantine church on the Greek island of Hydra, edited in-camera in the moment of filming.

The Swiss chateau built for Wagner by King Ludwig II is documented in Sorrows, an in-camera film composed through intricate layers of superimposition.

In his last years, working quietly in Europe, Markopoulos re-edited his whole body of earlier films and dozens of new ones he had shot and edited (but not printed) into one magnum opus, Eniaios. It is one of the longest films ever made: the complete film lasts approximately 80 hours and is divided into 22 cycles. Markopoulos toiled over Eniaios and completed it, but the film was never shown in his lifetime. At the time of his death in 1992, it remained unprinted. From the moment he began to construct it, it was Markopoulos’ intention that the film be projected only at the open-air site of the Temenos. After the filmmaker’s death, Robert Beavers set out to realize and properly showcase this epic work. He created the Temenos Archive and the not-for-profit organizations, Temenos Inc. and its Association. He has worked tirelessly to establish the screening events in Arcadia.

“In my film I suggest that there is no greater mystery than that of the protagonists. War and Love are simply equated for what they are; the aftermath is inevitable, and a normal human condition, for which like the ancients one can only have pity and understanding. In this lies the mystery. All else is irrelevant. That there are other sub-currents of equal power in The Mysteries goes without saying; and, those who are capable of the numerous visual visitations and annunciations which the film offers them will realize what is the Ultimate Mystery of my work.” (Markopoulos, Disclosed Knowledge, 1970)