The work of Malcolm Le Grice is featured in an extensive season of screenings and events at BFI Southbank. Crossing the Threshold: Experimental films and live performances from Malcolm Le Grice begins with premieres of films recently restored by the BFI National Archive on Thursday 5 May 2016. The season continues throughout the month and includes live performances, multiple projections, and discussions.

Peter Gidal’s text on Le Grice’s film Yes No Maybe Maybe Not, reproduced below, was first published in ARK, Journal of the Royal College of Art, Spring 1970. It was revised in 1974, and subsequently included in the Structural Film Anthology, BFI, 1976 and 1978.

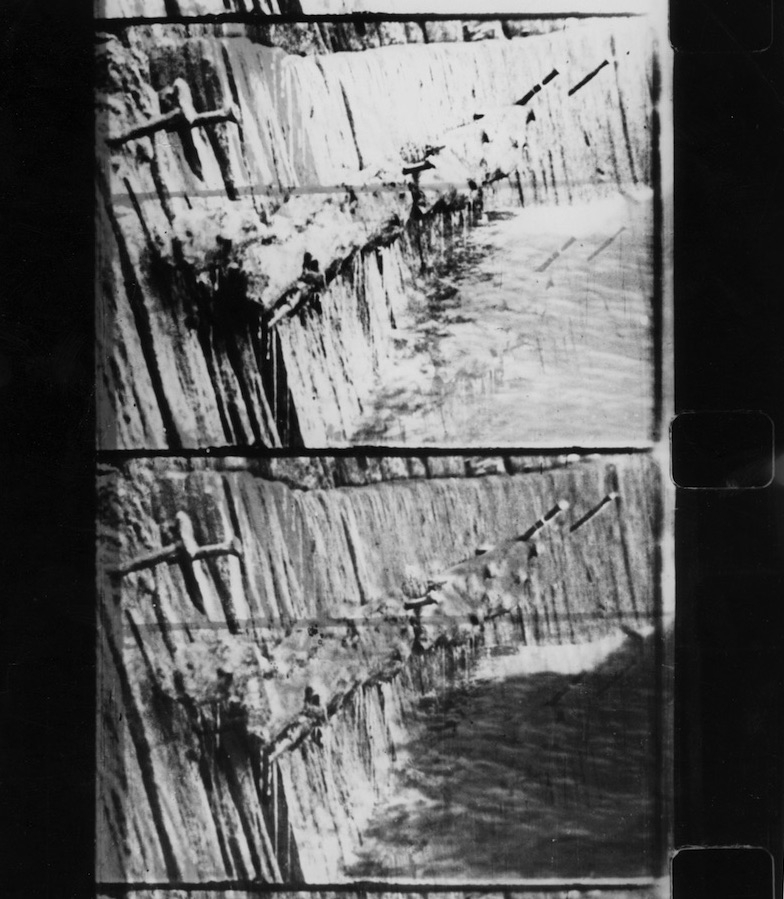

Yes No Maybe Maybe Not

There are two basic sequences. An image of water splashing against a wall or barrier, and a long shot of Battersea power station (with its huge smokestacks, smoke rising out of them). Through precise strategy, which includes, however, elements of chance, Malcolm Le Grice has set up this film. [b/w, silent, 12 mins., 1967.]

The film starts with a negative image of the water superimposed upon the image-positive. Then we see Battersea power station superimposed upon itself (again negative on positive.) Then we come to variations of the power station through a change in synchronization, the negative is held back about four frames, and the sync is lost, creating a space between the negative and the positive. Following this, the water is superimposed upon the Battersea power station, to give us a triple layer of movement. The space between two equal opposite images that are several frames out of sync makes for the effect of bas-relief; also, the separation of two images (one negative, one positive) makes for a line-determined space of grey that varies in shape and tone according to the change of synchronization (moving, that is to say, the negative another 5,6,7,8 frames ahead of the positive). The interplay of same images creates the dialectic.

The larger the difference between two ‘same’ images (negative over positive) the larger the grey in-between shape becomes. Out of the space between two shapes we create a new image. As this new image is the product of the space usually considered a negative area formed by the separation of a negative and a positive image-layer, one cannot immediately grasp hold of the precise situation when watching it. To add to this, the second image, of Battersea power station, involves itself to the same triple extent. The intermittent negative shapes formed (negative not in film terms but in terms of the leftover space created by the separation of two shapes, either on negative or on positive filmstock) are defined by line. The image of foreground and background becomes reversed, and through the abstraction process we lose sight of 3D space representation. Here the illusion is one that can be visually clarified. As we focus on a certain space, we become aware of the process of separation of image, and cannot help but react to this impulse. The process-viewing itself is the content of this film. This becomes apparent. The film consists primarily of a 30ft. (50 second) sequence of the water, and a 25ft. sequence of Battersea power station. After Le Grice (who printed this film himself in the labs) came to the end of each section, he would start over with the same piece of material. The images themselves are not found images. They were filmed by Le Grice to be used specifically for the film. They are not chosen images that serve a purpose in terms of any specific meaning prior (or anterior) to the film. The play of the horizontal waves crashing repeatedly against the barrier, together with the vertical chimney, makes for a complex (therefore intense) image in its own right.

The repetition in this film points to an obsessiveness. When the waves hit the barrier, again and again, with varying areas of intermittent shape formed by the negative/positive image, we are led on to a path of studiously becoming involved with precision of vision and nuance of change. The loop-effect, which can never be securely ascertained, makes for a gap in our knowledge: we do not know whether the splash of waves is a repeat of the splash two seconds previously. Is it similar, or is it the same? We become deeply involved in watching. We attempt to relate the negative image space to the positive image beneath it, or next to it, as it seems in the final marrying of the two sections. Film does, after all, consist of a combination of illusionistic three-dimensional space and two-dimensional ‘abstract’ space, and this film makes the most sophisticated use of both.

The obsessive repetition of image as question/answer dialectic is shown as part of the intention in the title of the film. This thought-process, the internalized dialectic with the self, the posing of question and anti-question towards ‘maybe not’ rather than an affirmative is clearly a preoccupation for Le Grice. Together with the other elements and in terms of inculcated response and visualization, this approach has found its purest formation in this film. It is a masterly example of the perfection of which this idiom is capable.

Peter Gidal