The Responsibility of the Cinema in Our Age

Today, the Cinema is still in its infancy. That is to say, that even with the monumental technical achievements in the mechanics of Cinema, we still lack a true form of Cinema. We lack a film form.

The Cinema began as a representative of the photograph, and as a representative of the Theatre. From the beginning until today it has been chaos. In the beginning there was fruitlessness in the attempts of the very early film creators as to how to utilize the monster known as the camera; for the camera is truly a monster. In reality the camera is the black spirit of Cinema, and the film creator must learn to anticipate its every attempt to dominate the original IDEA during the production of a film.

With this Cyclops of the one eye, the early film creators, such as the great Griffith, Ince, and later Stroheim, Eisenstein, and much later von Sternberg, Murnau and Dreyer gave us a sense of what film form might become. They each gave us, according to their own individual tastes, a sense of the well proportioned, and the well composed film image. But within this film image there were obviously people who had to move, to play-act, and there it seems to me the Cinema has remained to this day.

Of course, sound was born, and the various types of screens came into existence, but these have not helped the Cinema. The pictures are becoming continuously larger, and the sound continuously louder. The appeal is to the appendage eye and ear; not to the heart which as Schiller said, “Gives Grace To Every Art.”

For me, the Cinema lacks a soul, a psyche. It is no longer necessary to make films from ordinary adaptations and cheap novels. We have the urgent themes of a universal world and of our own era to present upon the screen; and, for each of these, the Cinema needs a particular form of presentation.

On the stage the actor’s movements are exaggerated to give the distant meaning which is assumed takes place between the actor and the Theatre spectator. It is said that the Theatre is intimate. It is not. There is nothing more distant than the Theatre spectator, and especially the Theatre spectator of today, and the actor. The actor as IDEA. And yet, in the Cinema which is so often accused of not being intimate, yet it is intimate, there is the focus of attention between the film image and the eye of the spectator. In fact the focus of attention is so great, that if used properly, and according to a set of rules proper to each individual film creator’s purpose, the Cinema can reach the very seat of the film spectator’s psyche.

If in the Theatre the parts of the body are used by the actor for exaggerated purposes, in the Cinema the parts of the body should be utilized by the film creator to reveal the action. The film creator if he wishes to use an eye, must not only use the eye, but the parts of the eye. If the lips are to be used, the features of the lips themselves should be utilized. If it is a matter of smiling, it must not only be the smile which is utilized, but the very parts which make up the smile. Further, if it is a matter of running, jumping, walking, slipping, dancing, each part must be related to the film creator’s original IDEA. The original IDEA in a given film work must be consistent in the words, if words are used, in the coeval use of sound, in the use of the proper lens, in the need for music, and even in the lesser uses of costumes and sets; both interior and exterior.

Each film creator must be morally responsible for his work, whether it be narrative, lyrical, or epic. Film creators must create for the world they live in, and from which they perceive each work. The danger in any work lies in the fact that the creator believes only in himself.

For me, personally, the Cinema is music; is music with its contrapuntal elaborations. Cinema is the noble metaphysical Art of our age, and of our one world without boundaries. Cinema can show us in what aspects we differ from one another, and in what aspects we remain the same. Cinema can draw nations together, and dissolve boundaries between groups of men. Lastly, Cinema is the representative of Life which no other Art can give us, so truly.

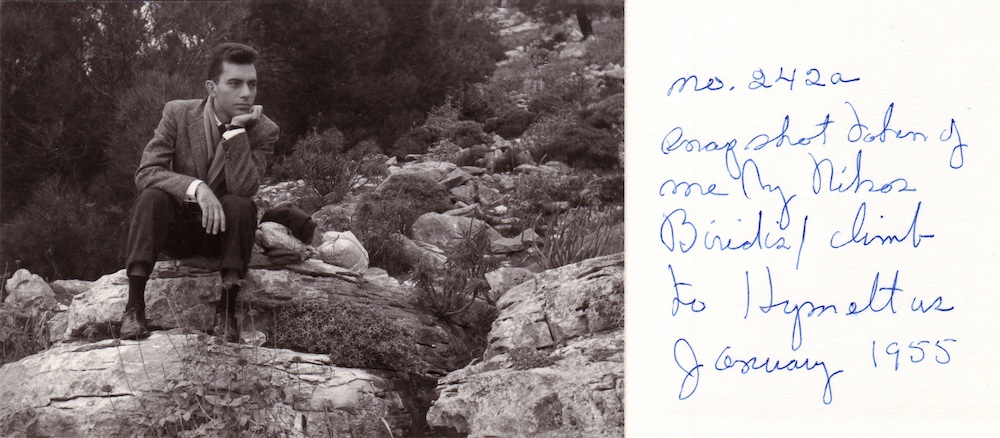

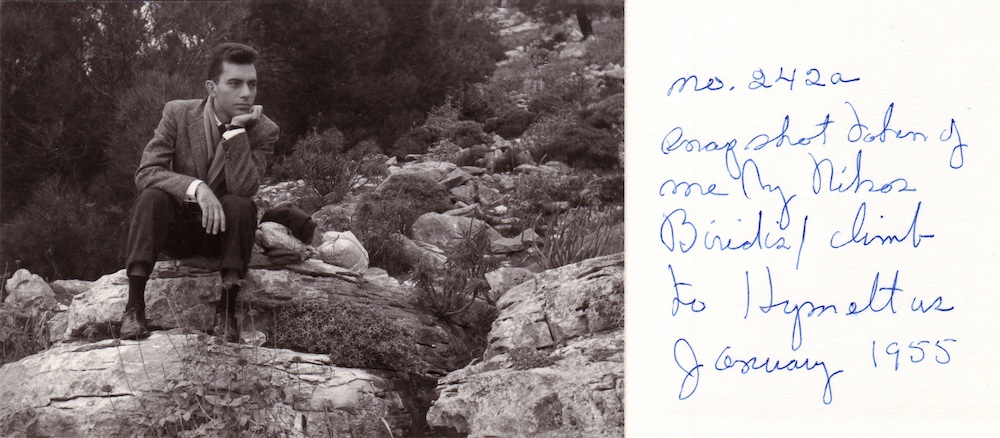

This text was delivered as a lecture at a meeting of the Nea Estia Society, Athens, 21st of December, 1955.