Thom Andersen Retrospective

4–12 April 2018 at CGAI, La Coruña, Spain

“The cinema must restore our belief in the world (…) before or beyond words”

(Gilles Deleuze)

Unha das expresións máis estrañas da cultura contemporánea é a cinefilia no seu sentido mais puro: o amor ao cine. A cinefilia é algo que se vive, que se transmite, que se trata co extremo coidado das cousas fráxiles. Os filmes bos salvan a vida dos cinéfilos, repoñen unha certa bondade intrínseca do mundo. Se non fose polos filmes, polas clases ou polas palabras, polo menos Thom Andersen sería un cinéfilo, alguén que non distingue no mundo o cine do non-cine.

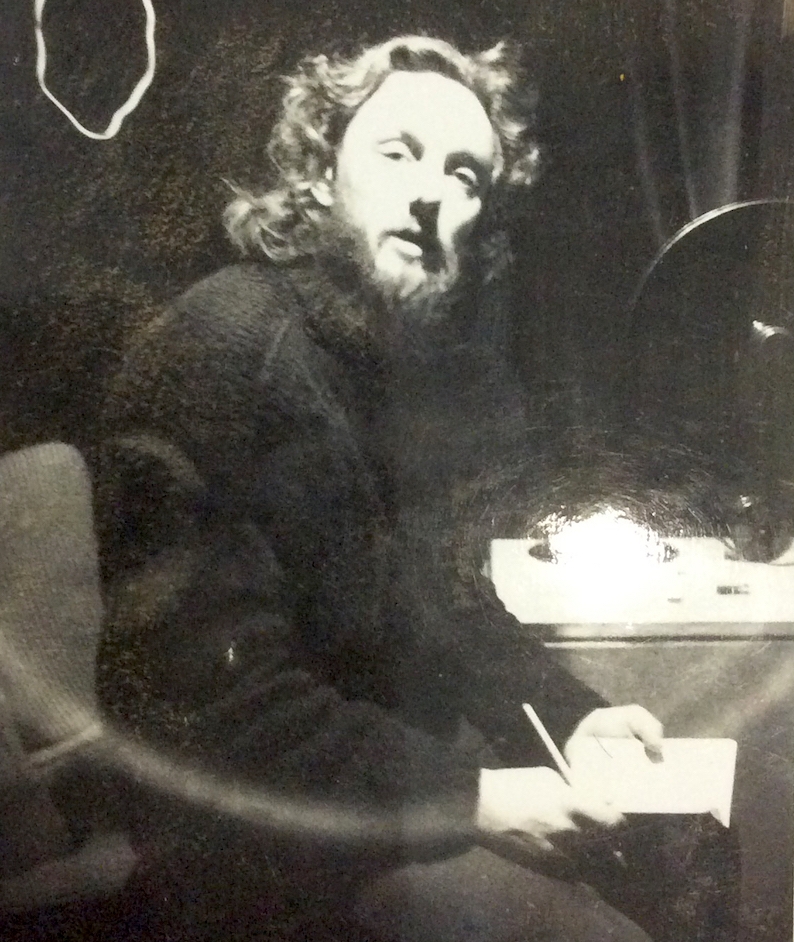

Profesor da prestixiosa CalArts, escola de arte nos Ánxeles, Andersen, nado en Chicago no ano 1943, é un cineasta de afectos que compón unha filmografia non moi extensa, mais particularmente ben articulada e pensada con detalle. É talvez a súa faceta pedagóxica a que nos obriga, paseniño, a volver ollar para o cine ou para lugares de memoria (unha vez máis, non importa se eses lugares pertencen ás imaxes en movemento ou á realidade cotiá), descubrindo o que está detrás, a tensa política do mundo en cada rostro dunha estrela de Hollywood ou do mural comunitario perdido nunha calella dos Ánxeles. Formado na USC School of Cinematic Arts, dos Ánxeles, Thom Andersen fai os seus primeiros traballos académicos xa nos anos sesenta, coas curtametraxes Melting (1965), — ——- (1966–67) (tamén coñecida coma The Rock n Roll Movie) e Olivia’s Place (1966/74). É, porén, coa súa primeira longametraxe que o realizador produce o seu primeiro traballo con folgos, a analizar a arqueoloxía do cine nos traballos do fotógrafo, pioneiro e experimentador Eadweard Muybridge. Neste filme, Andersen mostra xa a súa agudeza na análise política das imaxes e da súa propia produción. Neste sentido, veremos, aquí e en filmes posteriores, a forma en que o seu traballo rescata as imaxes perdidas nos arquivos do tempo e olla para elas cunha nova mirada, comprometido nunha visión marxista do mundo: quen explora e quen é explorado. Por exemplo, com Red Hollywood, de 1996 (realizado con Noël Burch), Thom Andersen analiza os trazos comunistas de guionistas e realizadores que foron silenciados na historia do cine logo da caza de bruxas protagonizada polo senador Joseph McCarthy e da que resultou unha listaxe negra destes e doutros autores. Neste filme, o cineasta vai, pacientemente, desocultando esas imaxes e sons, vendo neles a marca da denuncia social e dun reverso total do cine de estrelas de Hollywood. É un filme de extrema pedagoxía (e foi editado tamén un libro homónimo) e lanza, definitivamente, o método de traballo que culminou na sua obra mestra: Los Angeles Plays Itself, filme que comezou por ser un conxunto de clases que Andersen impartía en CalArts.

Los Angeles Plays Itself é un vídeo-ensaio avant la lettre no que desmonta a representación do espazo no cine. Para Andersen, o espazo é un factor político porque implica unha relación do realizador co que é retratado. En Los Angeles, o cineasta mostra como a cidade é utilizada de forma caótica, anacrónica ou cómica, precisamente por ser a meca do cine e onde todos os estudios se atopan. Por iso mesmo, Andersen mostra os filmes verdadeiramente concordantes coa realidade do espazo, con aquilo que é mais fondamente identitario da cidade, en contraste con aqueles en que a cidade é un mero estudio para inventar outras realidades. O método será sempre o mesmo: extractos de filmes montados sobre unha voz en off cristalina, pedagóxica e mesmo irónica. É, así, a ironía unha das marcas do realizador, coma se só mirando desa forma fose posible afrontar a máquina industrial de Hollywood. A ironía é, moitas veces, asociada a unha asumida nostalxia – unha das marcas dun cinéfilo incorrixible: saber que o gran cine é raro e que o pasado encerra obras determinantes da historia da arte. Esa nostalxia, xunto a unha vertente mais política, está presente en Get Out of the Car, na que Andersen mostra como Os Ánxeles está nun proceso de agochamento do pasado. Curiosamente, esta curtametraxe é moi divertida – pelos apartes do propio Andersen – e a ironía está logo patente no seu título: Os Ánxeles – a cidade das grandes autoestradas – precisa volver mirar para si mesma, camiñar polas súas calellas e polas súas rúas.

A ruína, o pasado e aquilo que desaparece co tempo está presente tamén no filme máis portugués do cineasta: Reconversão, unha obra realizada en Portugal e sobre a obra do arquitecto portugués Eduardo Souto de Moura. Trocando o 16mm nostálxico de Get Out of the Car por unha técnica de timelapse inventada polo seu colaborador e cineasta Peter Bo Rappmund, en que o tempo parece suspenso, revélase como a obra de Souto de Moura é tanto construción coma ruína (é sintomático que unha das obras máis vibrantes deste documental sexa un edificio que o arquitecto proxectou sobre a ruína dun anterior proxecto seu).

O traballo de Thom Andersen pode ser comparado co dun arqueólogo que rescata as imaxes e lles dá novos sentidos, provocando unha revolta das propias imaxes, agora illadas e transcendidas das narrativas onde estaban inseridas. Iso é evidente en The Thoughts That Once We Had (2015), unha historia persoal do cine, que volve ao sentido pedagóxico-político de Los Angeles Plays Itself, mais agora nunha inclusión absoluta das imaxes en movemento e da súa historia. O filme é unha especie de gloria do cinéfilo, unha cobiza de ver o mundo a través destes filmes e con eles provocar unha ruptura co devir capitalista do futuro. Para iso, Andersen escribe no final deste filme: “To those who have nothing must be restored the cinema”. O cine como salvación do mundo é, pois, na cinefilia extrema de Thom Andersen, unha arma de revolución.

(Daniel Ribas, do catálogo de Posto/Post/Doc 2015)

A celebración do ciclo coincide coa recente publicación do libro de The Visible Press – Slow Writing: Thom Andersen on Cinema – editado polo prestixioso crítico especializado en cine experimental Mark Webber. Trátase dunha escolma de artigos do propio Andersen nos que reflexiona sobre o cine de vangarda, mais tamén sobre Hollywood ou autores internacionais como Yasujirō Ozu, Nicholas Ray ou Andy Warhol. Pódese atopar máis información sobre o volume no seguinte enderezo: http://thevisiblepress.com/product/slow-writing/