Peter Gidal: Condition of Illusion

22 September to 11 November 2017

80WSE Gallery, NYU Steinhart School

80 Washington Sq East, New York, NY 10003, USA

Free and open to the public on Tuesday-Saturday, from 11-6pm.

Condition of Illusion is Peter Gidal’s first solo exhibition (British b. 1946). An important theorist and writer, as well as a filmmaker since the late 1960s, Gidal’s work has been shown around the world including cinematic retrospectives at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1983, Paris’ Centre Pompidou in 1996 and 2015, as well as at Docpoint, Helsinki and at the Cinematek, Brussels in 2016.

Gidal has been one of the main proponents of Structural/Materialist Film and has long been associated with the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative (LFMC), which was founded in 1966 as an independent filmmaking organization. The LFMC’s formation was announced by a telegram sent to Jonas Mekas, a founder of the New York Film Co-operative, which declared an intention to “SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT STOP NEVER STOP.”

Despite these early connections, Gidal published correspondence with American film and art critic Annette Michelson in Artforum clarifying the separateness from North American structural filmmaking of the time.[1] Some of this was based on the rigorous opposition of structural/materialism to empiricism and depoliticized formalism. Gidal continually published polemical and theoretical essays which had their effects on experimental film practice, theory and writing, though never confusing intention and language with film’s own determinants and the processes of making, moment for moment. The split between perception and knowledge was always crucial.

This exhibition, a retrospective, is comprised of 16mm films, photographs, and text-based work, from 1968 to 2013 alongside new and unseen material. Never a mapping of theory onto the work, it follows the first anthology of his literary output, Flare Out: Aesthetics 1966-2016, edited by Mark Webber (The Visible Press, London, 2016). The wide range of topics includes film theory, leftist politics, Samuel Beckett, Thérèse Oulton, Gerhard Richter and Warhol; while discussions of his own films are largely absent. For the late artist and curator Ian White the problem with Gidal’s work becomes “how to describe the films themselves as they are precisely not about description, but about process, about something being produced not reproduced: not representational (although they do show recognisable things, sometimes) but anti-representational, anti-narrative—structural.” In a recent review of Flare Out: Aesthetics 1966-2016, Noam M. Elcott, draws from White’s remarks and concludes as to this distance from the pleasure of narrative techniques and resistance to the capital structures through which cinema might be otherwise understood: “Gidal and London Film Makers Co-Op (LFMC) forced aconfrontation with the politics and poetics of media infrastructure—a confrontation that is ever more urgently needed.”

The exhibition begins with Gidal’s installation Volcano, whichfollows upon the concerns that he has had for more than 30 years, namely the problems of representation/unrecognition in a representational medium. A series of ten large format photographs of cooled and fissured lava will be shown alongside the half-hour, silent 16mm film, shot on a volcano on Big Island in Hawaii (2003). This will be the first time that Gidal has presented work in still photography.At the center of this exhibition a compilation of four short films shown one after another in their original 16mm format—Key (1968, 10 min), Clouds (1969, 10 min), Hall (1969, 10 min) and not far at all (2013, 15 min). This begins with Gidal’s arrival in London in 1968 and ends with his most recent film produced in 2013, the offcuts of which became CODA1 and CODA2, wherein Gidal’s soundtrack consists of three lines from a 1000 word story written by Gidal in 1971, that had been cut up and read (unbeknownst to him) by William Burroughs, later on an LP and CD Break Through In Grey Room.

This deliberate and uneasy reproduction of language is also present in a new installation extracted from three different works. His film Condition of Illusion (1975, 32 min) includes sections from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable and a quote from the end of Louis Althusser’s On the Materialist Dialectic, which also appears in his 1975 seminal text “The Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film” neither necessarily coming before or after the other. In part it reads: “A ‘theory’which does not question the end whose by-product it is remains a prisoner of this end and of the ‘realities’ which have imposed it as an end.” The quotations that he uses in Assumption (1997, 1 min) have been slowed until readable, while all the images have been removed from Upside Down Feature (1967–1972, 62 min) including Man Ray’s photos of the dust on Duchamp’s Large Glass. Only the text elements will be shown here from Beckett’s essay on Proust, flashing (dimly) one word at a time; when after two-thirds of the text, presented upside down andbackward, switches to “straightforward” reading, the ideological difficulty of the norm becomes a relativist’s dream or at least question.

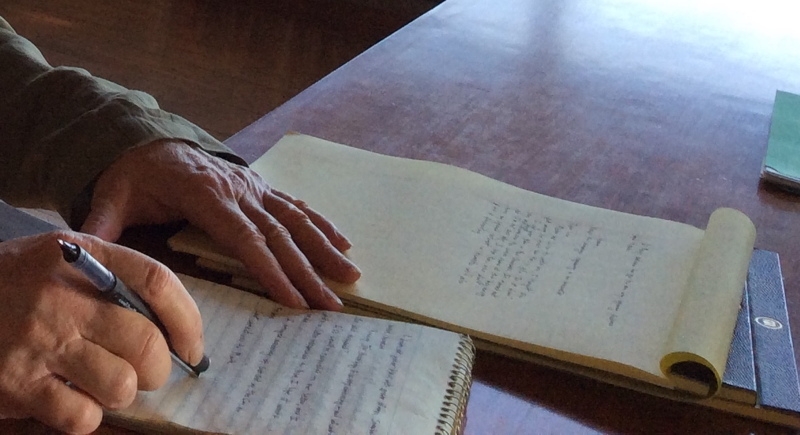

This sequence of rooms concludes with another unseen series of photographs that have been enlarged from images detailed in an album belonging to Gidal’s photographer uncle in 1930, created after a visit to Copenhagen, and forms the content of Gidal’s 1977 film, Kopenhagen/1930. George Gidal worked at the origins of modern photojournalism for Münchener Illustrierte, Vue, and AIZ: Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung. He died in a crash soon after he produced these images. Gidal inherited the contact prints with their Vertovian/Eisensteinian sequencing, numerically reordered “cinematically”—including handwritten German script commentary. In Kopenhagen/1930, there is a notable departure in attitude from Gidal’s earlier works, using here still images with frequent hints to the narrative film that could have been. In addition to the works on display in Condition of Illusion, Gidal’s iconic work Room Film 1973 (1973, 55 min) will be screened on select Wednesday evenings.

Gidal’s work is influential to several generations of film artists and writers, from those he taught advanced film theory at the Royal College of Art in London between 1971 and 1983, as well as those working there in Environmental Media, to a more recent generation. Writer and artist Tom McCarthy described Gidal’s practice as follows: “It’s upside down, inside out, negative, reversed – as though Gidal had cranked all the navigational tools of his medium to their absolute zero, and in so doing, groped his way towards a spot that’s not on any map, some true, magnetic north of cinema itself. The viewer, held in this liminal space, this threshold, is by turns (or simultaneously) mesmerized, disoriented, captivated, frustrated and delighted.”

[1] Annette Michelson, Peter Gidal, and Jonas Mekas. “Foreword in Three Letters,” Artforum, September 1971

Peter Gidal (British) was born in 1946 and grew up in Switzerland. He studied theatre, psychology and philosophy, at Brandeis University, the University of Munich, and the Royal College of Art in London. Only his first film Room—Double take (1967) was made in Massachusetts, while all the rest in London.

Books by Peter Gidal include Understanding Beckett: A Study of Monologue and Gesture in the Work of Samuel Beckett (Macmillan, 1986), Andy Warhol: Films and Paintings (Studio Vista/Dutton, 1971), Structural Film Anthology (BFI, London 1976), Materialist Film (Routledge, 1989), and Andy Warhol: Blow Job (Afterall Books, 2008), as well as an anthology containing fifty years of Gidal’s writings, Flare Out: Aesthetics 1966–2016 (Visible Press, 2016).

Gidal’s films have been screened in two dozen countries, with in-depth programs at the Tate Gallery, London; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Royal Belgian Film Archive and Cinematheque; Documenta; the Riga Avant Garde Festival, Doku Festival in Finland, and Arte Inglese Oggi, among others. Gidal was awarded the 1974 Prix de la Recherche, Toulon, and the Prix de l’Age d’Or in Brussels in 2016, as well as the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2016 Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. He co-founded the Independent Film-makers’ Association in 1975, and taught postgraduate advanced film theory at the Royal College of Art, London, for twelve years until 1983.

Condition of Illusion is curated by Nicola Lees, director and curator of 80WSE Gallery with assistance from Jessica Barker, Ben Hatcher and Hugh O’Rourke.