“Some Introductory Notes on Gidal’s Films and Theory” (1979)

My work and Gidal’s has frequently been bracketed together, most recently under the term Structural/Materialist (a Gidal formulation) – the bracketing being applied equally to the films and theoretical writing. This double harness has caused us both some problems, obscuring the differences between our work; none the less, with the level that the public critical debate has reached, I would rather have my position confused with his than with any other film-maker. Which is to say, as the lines are drawn to date, in spite of our differences, there are considerable areas of agreement between us. In the strict sense, we have never developed a joint position nor presented any co-operative manifesto, but we have had many long conversations over the last decade which have influenced the development of our positions considerably.

It would be impossible to trace the path of those discussions, the effects of which have become incorporated in our work, but it is partly to develop some of the thoughts which have passed between us recently that I am writing this introduction. As Gidal pointed out when he asked me if I would do it, I have never written on his work at any length (nor he on mine for that matter) – though we have been publicists for each other. I could not let this preamble pass without pointing out that if the fact of film-makers writing on each others’ films seems a little incestuous – before cries of nepotism – if some of the critics in this country had spent a little more time on the current British film culture we could have spent more of our time on film and theory and less on publicity, reviewing and polemics.

Our most general area of collaboration, which I will not dwell on, has concerned the development of the working context for experimental film. We have both been deeply committed to establishing conditions for production, presentation and distribution of independent film in a pattern radically different from that of the dominant film industry. Gidal, like myself and a number of other avant-garde filmmakers, has put a considerable amount of time into these issues through entirely practical and frequently mundane tasks mainly within the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, but also within the Independent Filmmakers’ Association and on committees in the British Film Institute.

Our most general area of agreement has been a deep hostility to the way in which international capitalist corporations have controlled the development of film culture and the effect this has had on the predominant assumptions about film structure. This hostility has been expressed variously as an opposition to narrative, illusionism, identification, catharsis and so on. As the dialogue between Gidal and myself has become more sophisticated, some of the approaches to these oppositions have differed in detail, but the underlying resistance to compromise with the forms and mechanisms of dominant cinema remains common. If my own recent films have related themselves overtly to the problems of narration, identification and cinematic illusion, it is because I have encountered them (perhaps in error) as a consequence of the direction of my work.

Gidal has maintained a more distinctly oppositional stance, certainly at the level of theory, frequently expressed in the prefix ‘anti-’ (anti-narrative, anti-illusion), and while his films would seem to maintain this opposition into their construction, they are more problematic in this territory than the diametric rhetoric would suggest. On the other hand, his major theoretical work, the “Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film” and its extensive footnotes, traces many of the difficulties and complexities this oppositional enterprise encounters.

To deal with Gidal, it is necessary to consider both his work as a film-maker and a theorist. He has referred to Althusser to support the independence of the two practices and he has further pointed out how historically there have regularly been discrepancies between artists’ work and their theorisations and rationalisations. Whatever the independence, one from the other (and it is clear that they are distinguishable discourses), in Gidal’s case they should be related to each other. Not only does the theory seem to address some of the films’ problems quite accurately, but he has particularly encouraged through the form of presentation of his work, that the achievement of the films, as it were, be tested against those aims defined in the theory.

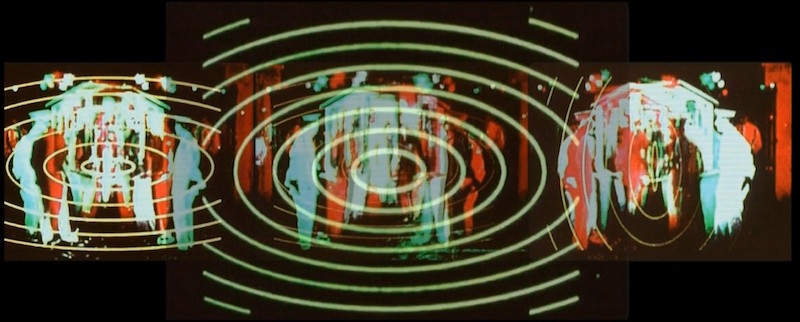

If we were concerned with a general review of Gidal’s work, then like with any other artist, his early films would be seen to contain many of the initial issues which become more clearly reworked later. However, without dismissing his earlier work, it is possible to encounter the most pertinent problems which he raises through reference to a few more recent films and his major theoretical text “Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film” (Studio International, November 1975). Any one of Bedroom (1971), Room Film 1973, Film Print (1974), Condition of Illusion (1975), Fourth Wall (1978), or Silent Partner (1977), can be studied and related to his major theoretical article, and while they are all different works in detail, their concerns are remarkably consistent.

Excerpted from the opening section of “Some Introductory Notes on Gidal’s Films and Theory” (1979) by Malcolm Le Grice. Originally commissioned for the BFI’s Independent Cinema Documentation File No. 1: Peter Gidal (November 1979), later republished in Millennium Film Journal No. 13 (Fall 1983) and Experimental Cinema in the Digital Age (BFI, 2001).